All profits donated to the charities of Amma.

All profits donated to the charities of Amma.

A couple of days ago, I watched the videos about Maharishi’s affairs on https://srm.news/hive/ and read much of SexieSadie.pdf. In my opinion the videos incontrovertibly establish that Maharishi had affairs with multiple young women over decades.

First, I want to acknowledge the brave women who came out to tell their story, and the others who contributed critical corroborating information. We might dismiss one, two, or three accounts as “unstressing” or a misunderstanding, but the amount and quality of first-hand testimony in these videos is overwhelming. I can’t see anyone viewing these with an open mind not feeling the same, and I am someone who for the past 54 years held Maharishi in the highest regard and would dearly love for all this not to be true.

From skimming the SexieSadie.pdf, it seems these revelations understandably left some people disillusioned regarding the whole idea of enlightenment. In the initial shock, it certainly made me wonder as well. So I thought it would be worth reviewing some scriptural literature for possible clarification as to the nature of enlightenment.

I don’t intend this to be a bullet-proof argument or a scholarly paper. The scriptures I cite are just what came to mind without research. Hopefully, though, it might begin to shed some light on the topic. I’m won’t address the ethical, psychological, or social issues raised by these revelations, or the past, current, and future state of the TM Movement. I’m just zeroing in on one narrow issue: what all this says about enlightenment, if anything.

Though my view of Maharishi is profoundly revised from what it was, I still consider him a gifted teacher. I benefited greatly from the knowledge he brought out. That has not changed. I am deeply grateful for that but also deeply saddened that he violated sacred trust with numerous female students, hurt them, and brought shame to the lineage and tradition of knowledge he represented.

I’ll start by looking to the Yoga Sutras, because it clearly delineates requirements for liberation. I don’t know of any Advaitic texts that so concisely offer the same. You can certainly deduce such requirements from various Advaitic texts, or from the Bhagavad Gita for that matter. The Yoga Sutras and Vyasa’s commentary, though, states them plainly.

Some might feel that the Yoga Sutras, rooted in Samkhya, is a dualistic system and doesn’t apply to Advaita and therefore cannot apply to full enlightenment. For what it’s worth, I am fairly certain that authentic kailvalya is full enlightenment, not just cosmic consciousness (more on this later), but even if that’s not the case, any enlightenment we might imagine beyond kailvalya must encompass kailvalya. Brahman consciousness, for instance, is living the wholeness of life that is more than the sum of the parts, and per Maharishi’s own teaching, the parts include all previous states of consciousness. (See his lengthy YouTube video on Brahman consciousness.) It stands to reason that the requirements for kailvalya must then also apply as minimum requirements for any higher or ultimate state of enlightenment.

To set a bit of context, from Vyasa’s commentary on verse III:51 of the Yoga Sutras, he describes 4 classes of yogis:

Just for convenience, I copied the Sanskrit names of the seven ultimate insights and parenthetical translations of those names from https://www.yogabasics.com/learn/philosophy-of-yoga/jnana-bhumikas-the-seven-stages-of-wisdom/ . I’ve replaced their modern-day definitions with those provided by Vyasa from his commentary of Verse II:27 of the Yoga Sutras, which cut to the heart of each of the insights. Then I’ve added my own brief explanation in parenthesis to some. These might seem a bit technical. Sorry about that. The good news is they pinpoint specific critical underpinnings of enlightenment. Note they aren’t about external renunciation. That’s what’s great about these: they describe the subtle facets of a yogi developing detachment on the level of consciousness. It’s independent of lifestyle.

Note that the attainment of these 7 insights doesn’t seal the attainment of Kaivalya but brings you to the brink of kailvaya. That is, once you have these, you are in the 4th class of Yogi, Atikranta-bhavaniya, still working on eliminating the action of the mind. As Vyasa concludes in his commentary to verse II:27:

When these seven insights are acquired, the Yogin may be called Kushala or proficient. When the mind disappears, the Yogin can be called a Mukta-kushala or liberated one, because he then transcends the gunas.

So for Kaivalya, you not only need the 7 ultimate insights, but your mind must disappear, not temporarily, as in transcendental consciousness (that’s already achieved with the 3rd ultimate insight), but permanently. This is one reason I equate kailvalya with full enlightenment, as the Ribhu Gita, Ashtavakra Gita, and I’m sure many other Advaitic texts hold that with disappearance of mind, the world effectively disappears (as having substantial reality) and there is only Brahman. In fact, chapter 17 of the Ashtavakra Gita (an Advaitic text) is explicitly all about Kaivalya. The mind definitely doesn’t disappear in cosmic consciousness, so cosmic consciousness is not Kaivalya. It also doesn’t disappear in unity consciousness, so unity consciousness isn’t Kaivalya. It is said to disappear in Brahman consciousness. So Brahman consciousness either is Kaivalya or at least shares with Kaivalya this fundamental requirement for enlightenment.

This begs the question, what does it mean for the mind to permanently disappear? I think most reading this have experienced enough growth of consciousness to have a sense of this. In ignorance, the mind rises in large thought waves. The more the Self dominates your awareness, the “thinner” the mind becomes. As pure consciousness infiltrates every nook and cranny of the mind over decades of practice and the gradual growth of higher consciousness, these thought waves thin and become fainter and fainter ripples in the unbounded ocean of pure awareness (with eyes open, in activity). From this, it’s easy to imagine that in Kaivalya or Brahman consciousness, thought waves are negligible virtual ripples in the vastness of the infinite Self, Brahman. The mind has effectively disappeared. This is admittedly just a hint that deserves a deeper look at another time.

Back to the seven ultimate insights, verse I:16 of the Yoga Sutras summarizes them in a single statement. Especially because of Vyasa’s commentary, it’s worth citing:

Indifference to the gunas or the constituent principles achieved through a knowledge of the nature of the Purusha is called paravairagya (supreme detachment). 1:16

Vyasa’s commentary:

Through the practice of the effort to realize the Purusha principle, the Yogin having seen the faulty nature of all objects visible or described in the scriptures, gets a clarity of vision and steadiness in sattvika qualities. Such a Yogin, edified with a discriminative knowledge and with sharpened and chastened intellect, becomes indifferent to all manifest and unmanifested states of the three gunas or constituent principles.

There are thus two kinds of detachment. The last one is absolute clarification of knowledge. When detachment appears in the shape of clarified knowledge, the Yogin, with his realization of the nature of Self, thinks thus: “I have got whatever is to be got; the afflictions that have to be eliminated have been reduced. The continuous chain of birth and death, bound by which men are born and die, and dying are born again, has been broken.” Detachment is the culmination of knowledge, and Kaivalya (or liberation) and detachment are inseparable.

You can now draw your own conclusions on Maharishi and his behavior, and on what enlightenment actually requires. For me, the preceding establishes that Maharishi could not have been enlightened. His behavior demonstrated a lack of even the first 2 of the seven ultimate insights. It also helps to clarify the necessary character of a jivan mukta (one liberated while alive).

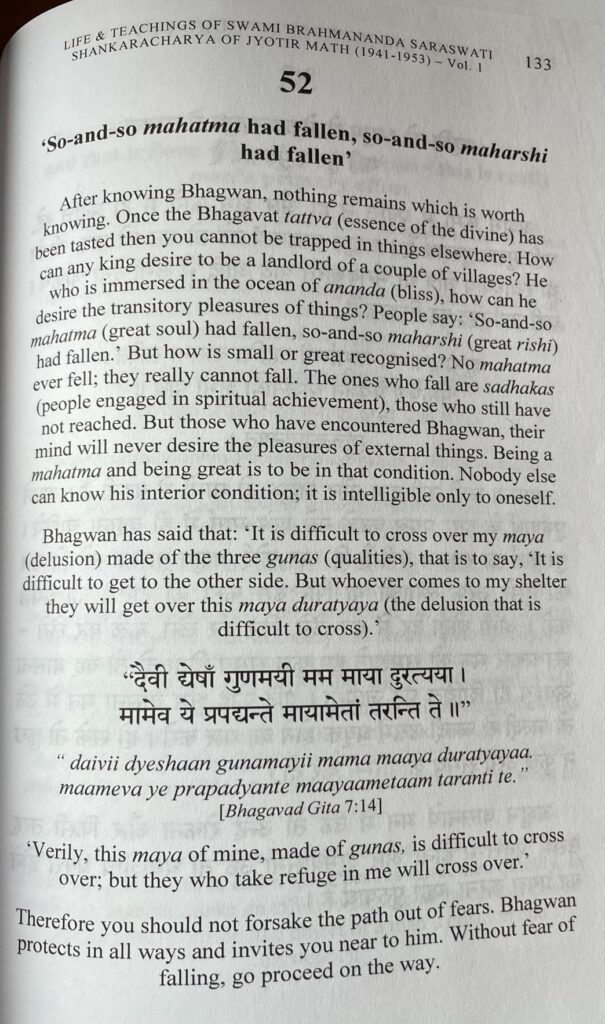

To complete this picture, here’s a page from 108 Discourses of Guru Dev (Vol 1) translated by Paul Mason. It addresses the question of whether a true Mahatma or Maharshi can fall. (For those who don’t’ know, Guru Dev was a renown Shankaracharya of Jyotir Math and Maharishi’s guru.)

If we give weight to these words, it was not lesh avidya (faint remains of ignorance) that brought Maharishi down. It was actual avidya and other kleshas (attachment, etc.) In other words, he wasn’t enlightened. Forget the lesh avidya excuse. Maharishi’s behavior certainly warrants a closer look at what constitutes authentic enlightenment. That doesn’t mean it should contribute to defining enlightenment or negate the possibility of enlightenment. The errant behavior of a sadhaka is irrelevant to enlightenment. Yet it is an invaluable object lesson for everyone on the path, even more so for those who believe they’re at the goal.

Another casualty for some that contributed to the SexieSadie.pdf was the validity of renunciation as a spiritual principle, especially as embodied in the M group. Maharishi had initiated dedicated teachers into lifelong celibacy (those in the M group), while he enjoyed sex with young ladies. It’s understandable this would be devastating to those M Group teachers and to subsequent Purusha and Mother Divine members. Yet ultimately the scandal has no bearing on the legitimacy of brahmacharya or renunciation as spiritual principles.

So many scriptures support renunciation as an essential spiritual principle. For instance, the first line of the Sanyasa Sukta from the Kaivalya Upanishad (one version here: https://archive.arunachala.org/docs/veda-parayana/na-karmana):

Na karmana na prajaya dhanena tyagenaike amritatvam aanasuh

Not by action, nor by progeny or wealth, but by renunciation alone have people attained immortality.

Shankara’s commentary on the Gita states that Karma Yoga is to purify and prepare for knowledge and renunciation, which are the actual conditions for liberation. This is so prominent a feature of Shakara’s commentary, it’s not worth the trouble to cite examples. Just pick up the Gita with Shankara’s commentary and start reading. Shankara’s emphasis on renunciation entirely agrees with Patanjali’s and Vyasa’s emphasis on paravairagya. This is the necessary support of renunciation and in turn liberation. What of enlightened householders like Janaka? Their inner state was one of renunciation, as texts like the Ashtavakra Gita make clear.

In fact, this is an important point. As I mentioned earlier, actual renunciation/detachment is an internal state. The seven ultimate insights are all about developing that, not about adopting a reclusive lifestyle. That internal state is essential to enlightenment. Why? Attachment to sensory objects is inimical to enlightenment because enlightenment sees the lack of substance to those objects and abides as the infinite, which is bliss. So how can it be attached to those objects? Only if still in ignorance. This is just another way of saying what Guru Dev said earlier. Outer renunciation may be conducive to developing inner renunciation, or not. This depends on the person. It is an entirely legitimate option for some.

The scandal of Maharishi’s behavior may gut the spirit of these internal TM renunciate groups. The movement can adopt a policy of denial, which commits them to a fragile course likely to fail by continued attrition. Alternatively, they can open to honest examination of facts and construct something new, transparent, and more vital. Many spiritual communities have had to go through this in recent years with positive results.

Another theme expressed in SexieSadie.pdf was a wish to return to God/devotion to God (as opposed to seeking enlightenment). Of course! Read the above passage of Guru Dev’s words. It’s the experience of God that quenches any thirst for sensory pleasures. Throughout Guru Dev’s recorded sayings in Paul Mason’s translations, he promotes devotion to the devotee’s Ishta Devata. Maharishi scrubbed this fundamental message from his teachings to keep them palatable to as wide an audience as possible. I don’t doubt that ultimately this very thing may have been the source of so much of the movement’s malaise.

This reminds me of a verse from the 12th Book of Shrimat Bhagavatam, Discourse12, verse 53:

Naishkarmyam apy acyuta-bhaava-varjitam

na shobhate jnaanam alam niranjanam

Wisdom that it is a direct means to Liberation does not adorn your soul if it is devoid of devotion to the Lord.

Yet it’s not an either/or choice between enlightenment and devotion. IX:22 of the Bhagavad Gita expresses perhaps the highest spiritual ideal:

Those who, meditating on Me as non-separate, worship Me all around. To them who are ever devout, I secure gain and safety.

Shankara’s commentary points out the specialty of such a state, which combines enlightenment with devotion:

While other devotees work for their own gain and safety, those who see nothing as separate from themselves do not. Indeed, these latter never cherish a desire for life or death; the Lord alone is their refuge. Wherefore the Lord Himself secures to them gain and safety.

Many verses in the Gita (and other devotional scriptures) pertain to devotion to God in enlightenment. I personally think that this is an area that we should explore, understand, and live.

Maharishi was a brilliant, charismatic teacher. He hurt some and helped many. I don’t recall him ever declaring that he was enlightened, but most of us around him assumed it. I do recall him advising never to talk about your own state of consciousness, saying that it was your business alone. Though there was plenty of inherent enlightenment signaling in his talks, to my knowledge he personally adhered to this advice. He also noted that only time will tell whether a person is really enlightened or it’s “just unstressing.” When asked how much time, he replied, “Any amount of time.” This perhaps foretold this very situation: “Any means any.” In Maharishi’s case, an entire lifetime passed before the truth came out. It’s a humbling, cautionary lesson, especially for those who would aspire to the highest.

As far as Maharishi’s behavior making a damning statement on enlightenment, it doesn’t. It does, however, highlight that despite all our decades of talking about cosmic consciousness, God consciousness, unity consciousness, and Brahman consciousness, we should question whether we have really understood the traditional requirements for enlightenment. I’m not aware that anyone in the TM Movement ever even stated them. Even though this article may fill in some holes, it doesn’t complete the picture. The intersection of the Divine and humanity is a topic as vast as Brahman, and all the world’s spiritual literature has not yet fully defined it.

Alladi Mahadeva Sastry, translator, The Bhagavad Gita: with the Commentary of Sri Sankaracharya, Samata Books, Madras, 1977

Goswami, G.L. Sastri, translator, Shrimad Bhagavata Mahapurana, Part II, Mitilal Jalan at the Gita Press, Gorakhpur, India, 1971

Mason, Paul, 108 Discourses of Guru Dev: The Life and Teachings of Swami Brahmananda Saraswati, Shankarachary of Jyotirmath, Vol I. Premanand, 2009

Swami Chinmayananda, Ashtavakra Gita, Central Chinmaya Mission Trust, Mumbai, 1997

Swami Hariharananda Aranya, translated by P.N. Mukerji, Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali, State University of New York Press, Albany, 1983